People are living there – a story of resilience

September 11, 2019

HOW TO DO AND PRESENT LOCAL HISTORY

October 10, 2019Writer

Dr Robin Lee

One of the frequent visitors to Hermanus in the early 20th century was James Douglas Logan (1857–1920). A writer has called him ‘the ideal colonist’, and that is true.

In the mid-to late-Victorian era, Britain produced colonists in large numbers. The essential components were: an interrupted education, earning income by the early teens, feeling trapped by the class system, ambition to ‘better’ oneself, down-to-earth attitudes, strong capitalist ethos (though they probably couldn’t spell that word), and a drive to win in business and personal relations, often not playing entirely by the rules.

But, they needed a more flexible social structure that did not close most opportunities to the working classes. The colonies offered this.

Sir William Hoy (1868–1939) had some of these characteristics. But they are seen most clearly in Logan who, like Hoy, was born in Scotland. The son of a railway clerk, he received only a few years of schooling before he was called on to augment the family income. He took up employment as a railway clerk, with every prospect of remaining one all his working life.

The first indication of his ambitious nature came when he quit this job in 1874 and ran away to sea. Two years later the ship he was aboard had to enter Simonstown Harbour for repairs, and Jimmy (as he was always known) took the £5 wages he was due, walked to Cape Town and started working – you’ve guessed it – as a railway clerk. However, the Cape Government Railways saw his potential and promoted him rapidly. Within a year he was promoted to the position of Stationmaster at the newly-built Cape Town Station.

In 1878, Logan was offered the position of Superintendent of a section of the railway between Hex River and Prince Albert. This was a significant boost to his career and income. But there was a problem. The job was at an isolated location, and the Railways thought it prudent that the man appointed should be married or become married within three months of being selected.

Down-to-earth Logan immediately courted and married Emma Haylett, a hotelier’s daughter. He couldn’t have known how useful her skills would become later in his career. However, he had another inducement – every account of Emma Haylett mentions how beautiful she was. Logan took up his new post well within the three months allowed.

Within a year, Logan had been awarded the catering concession for the Touws River Station, and by 1881 his business activities were large enough for him to resign from the Railways and get the refreshment concession for some other stations. Emma and James became frequent visitors to Hermanus, and it is worth looking at the connections that led to this.

The first connection is fortuitous. Between 1904 and 1910, the Luyt family (PJ and his first wife, Dollie) had employed an English family, the Taylors. Joey Luyt gives us the background of the house-keeper they called “Tay”:

Clara Taylor was born in Yorkshire. She and her husband came out to South Africa from England before the Anglo-Boer War to work for Mr Jimmy Logan at Matjiesfontein. Mr Taylor ran the restaurant at the Railway Station, and his wife worked as a housekeeper at the hotel there. After a few years, they went to Vryburg and then to Mafeking. They were in the siege of Mafeking and, after the town was relieved, they trekked by ox-wagon to Kimberley. They remained in charge of the station restaurant at Kimberley for some time and then decided to go to Rhodesia. They became ill on the train from food poisoning and, on arrival at Bulawayo, were taken to hospital. When Mrs Taylor recovered, she was told that her husband had died and had been buried in the local cemetery. Grief-stricken, she returned to Cape Town. John (Luyt) and Dollie had just taken over the management of the Marine Hotel, and she was engaged as a housekeeper by them.

After a controversial business career, Logan had retired in 1910 and had time to visit Hermanus. Again, Joey Luyt records the fact:

Mr Jimmy Logan, of Matjiesfontein, often came for weekends. ‘Tay’ was very excited the first time he came and was delighted when he remembered her. I gave him succulents for his garden at Matjiesfontein. Mr Logan owned the village as well as the hotel and had many famous persons as his guests, including Lord Milner and Cecil Rhodes.

By way of an employee and friend, Logan and the folks at The Marine were linked.

The second connection with Hermanus I have not been able to verify, but it is very likely. Hoy worked for the Cape Government Railways at precisely the time Logan did, and they must have met each other. Doubtless, Hoy told Logan about this quaint fishing village and his plans to forbid the extension of the railway to it, to preserve its fishing village atmosphere.

Logan would have been appalled. For him, railways were the future and a source of wealth. The closer he could get to them, the sooner he would become super-rich. He went the opposite way to Hoy. In 1884, he applied for and won the contract to supply refreshments to travellers on his station. Within a year, he was making so much money from his catering service that he resigned from the Railways and bought 3 500 morgen around a tiny main-line station called Matjiesfontein.

The Logan family settled there and began to develop a model farm and a village, which he owned. He also aimed to extend his catering business to all stations served by the Cape Government Railways. He used his contacts within the business and political communities to persuade Mr (later Sir) James Sivewright to grant him this monopoly for 18 years, without advertising the tender or consulting any of his Cabinet colleagues – perhaps, an early case of ‘state capture’?

This led to a massive scandal that brought down the government in the Cape Colony. Rhodes had to reconstitute his Ministry, omitting anyone remotely linked to the a?air. John X Merriman,

later Prime Minister, wrote about the concession: “It is a blackguard business – and the more you stir it, the nastier it smells.”

Logan did not suffer any public punishment for the venture, and during this period, seems to have been popular with Cape Town citizens, because of his sponsorship of South African cricket teams to play England. This phase of his life has been well-described by Dean Allen in his book, Empire, War and Cricket in South Africa, published in 2015.

Logan has been described as a “legendary litigant” because he used the courts to attack his competitors and those who threatened his business operations. A legal expert has analysed and documented all cases involving Logan from 1885 to 1912. Ten substantial cases are recorded, of which Logan was successful in seven and not substantively defeated in the other three. In one of the cases, Logan won a decision against Sir Alfred Beit, in another, he came out winner over Barney Barnato, and a third case went to the Privy Council in Britain. Logan won again.

Space constraints do not allow me to deal with two other interesting aspects of his life here, namely the full story of Logan’s cricketing tours and his role in the South African War. However, it is evident that this frequent visitor to Hermanus in the early 20th century had an eventful life elsewhere. Logan died in 1920 and is buried at Matjiesfontein.

The Marine Hotel in 1944.

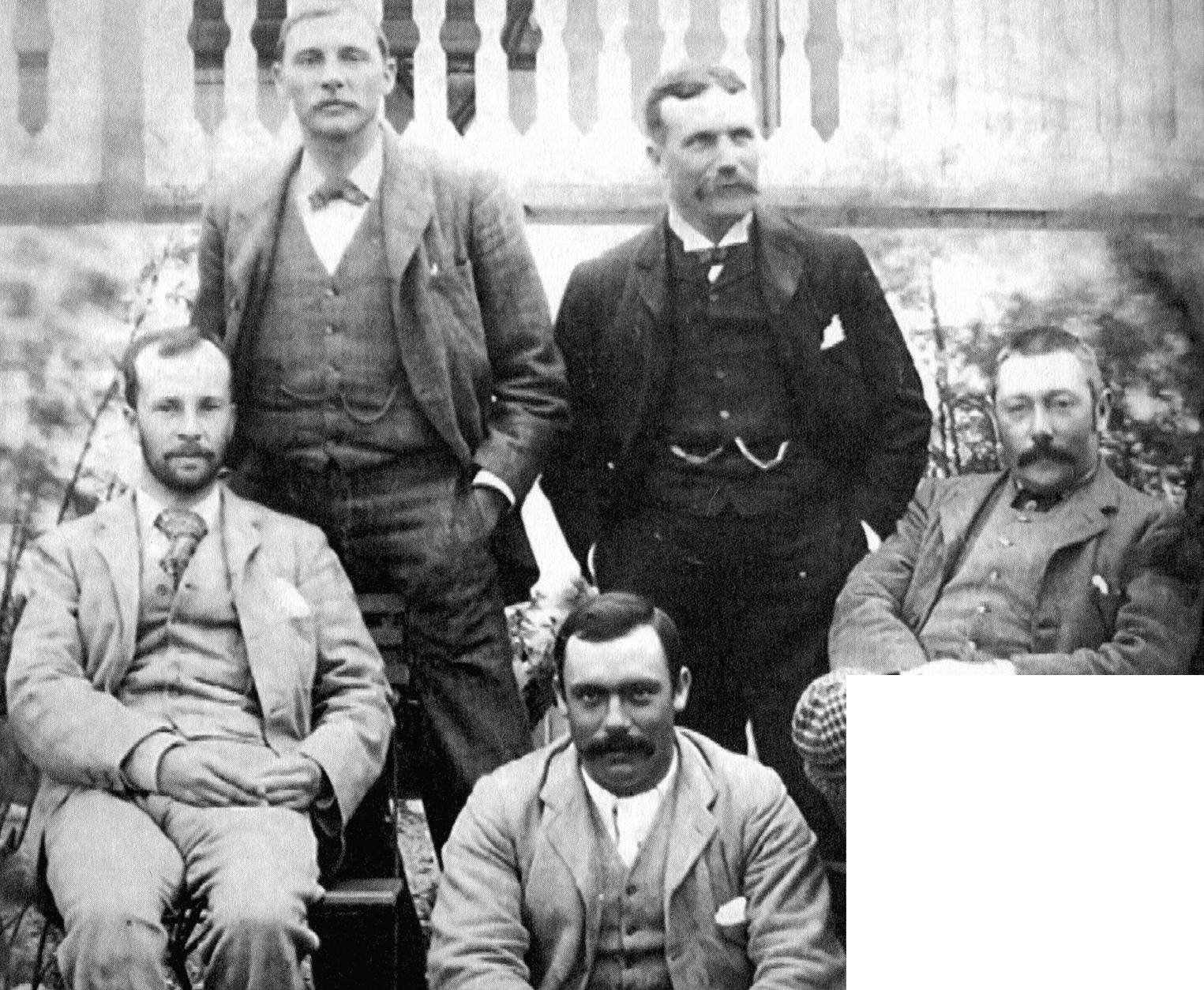

James Douglas Logan (standing, right) with a group of English cricketers, circa 1895.

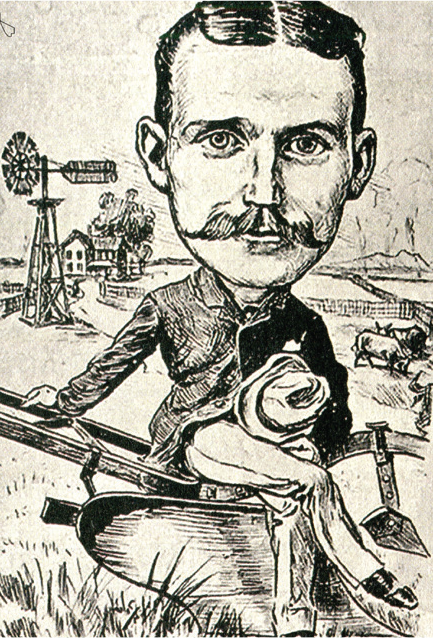

A caricature of Logan as it appeared in the Afrikaans media.