The right entrepreneur at the right time

Sir William Hoy was not only exemplary railway pioneer. His influence extended to fields such as electricity generation and even the founding of the Kruger National Park.

After the Peace of Vereeniging in 1902 William Hoy became Chief Traffic Manager of Central South African Railways (formed out of the Transvaal and Orange Free State railways) and had to deal with the contested topic of railway ownership.

The rapid growth of private railway systems in the USA in the late 19th century had created support for a private enterprise model.

Hoy believed that government should own and operate national railways, as it would offer services wherever they were needed and not just where they were profitable. State-owned railways could offer a range of services at least as well as any private operator might. It was largely due to Hoy’s convictions that the South African railway system was developed and has remained within the state.

Several challenges were presented to Hoy between 1902 and 1910. First, the issue of the gauge of railway track had to be decided and implemented, with agreement needed from the Natal and the two previous Boer Republics, without which costly trans-shipping of goods between trains running on different gauges would have to be made. Each railway system had vested interest in its gauge, but Hoy managed to broker an agreement that satisfied all parties.

On a smaller scale, several different systems had been started under local initiatives within the Cape and these had to be integrated into the Cape system and then into the national system. Hoy was successful in this as well.

Another innovation was introduced by Hoy that remained in operation until the 1990s. He realised that it would be uneconomic to try to build rail connections to smaller towns and villages. Rather, he believed that ‘railheads’ should be established at key junctions and a road transport system created to take goods further. In the case of Hermanus the railhead was at Bot River and the first railway bus to the town ran in 1912 – and hence no trains at Hermanus Station.

Hoy was also a strong advocate of the electrification of railways and, as early as 1922 wrote an article on the topic in the South African Railways and Harbours Magazine. However, the electrification could not begin unless an adequate electrical supply was available – and this was not yet the case in South Africa.

This situation opened up co-operation between the Railways and the relatively newly-established Electricity Supply Commission (which then had the English acronym ‘Escom’, which it kept until 1987).Hoy was involved in two projects that are amongst the earliest recorded: the electrification of the Cape Town-Simonstown route in 1927 and the construction of the Congella Power Station near Durban in 1928.

Hoy was involved in two projects that are amongst the earliest recorded: the electrification of the Cape Town-Simonstown route in 1927 and the construction of the Congella Power Station near Durban in 1928.However, the groundwork had been laid much earlier. In 1917 Hoy had invited experts on electrification from Great Britain to assess the South African system and advise him on the issue. The delegation and the South Africans designated to travel with them were given the use of Hoy’s private railway carriage during their stay. Their report was received in 1920 and immediately acted on by the government advised by Hoy, resulting in the creation of Escom in 1923.

However, the groundwork had been laid much earlier. In 1917 Hoy had invited experts on electrification from Great Britain to assess the South African system and advise him on the issue. The delegation and the South Africans designated to travel with them were given the use of Hoy’s private railway carriage during their stay. Their report was received in 1920 and immediately acted on by the government advised by Hoy, resulting in the creation of Escom in 1923.At this time Hoy was interviewed by a well-known American journalist, Isaac F Marcosson, who was writing a book on Africa. Marcosson’s impressions:

At this time Hoy was interviewed by a well-known American journalist, Isaac F Marcosson, who was writing a book on Africa. Marcosson’s impressions:

Stimulating the railway system of South Africa is a single personality which resembles the self-made American wizard of transportation more than any other Britisher… He is Sir William W. Hoy, whose official title is General Manager of the South African Railways and Ports [Harbours]. Big, vigorous, and forward-looking, he sits in a small office in the Railway Station at Cape Town, with his finger literally on the pulse of nearly 12,000 miles of traffic.

The creation of Escom enabled Hoy to press ahead with a joint venture between Escom, the Durban Municipality and the SAR to build the first electricity-generating station in South Africa, at Congella, just outside Durban, to supply power for the city, but also for trains hauling coal from Glencoe in northern Natal to Durban.

The station was built on land supplied by the Railways. Further investigation and experience, however, showed that it would be more economical to build a power station nearer the coalmines. The town of Colenso, on the Tugela River, was selected and, with Hoy behind the project, the work was completed in two years. At the time it was the second biggest railway electrification project in the world.

In 1922 Hoy became interested in the Kruger National Park – or the ‘Sabi Game Reserve’ as it was then called. He was consistently trying to increase tourism to South Africa and had instituted a ‘round in nine’ tourist train trip, from Johannesburg, through the then Eastern Transvaal and to Lourenco Marques (Maputo).

On the return trip an overnight stop was included at a place called ‘Sabi Reserve’ (now known as Sabi Bridge). Travellers were able to leave the train, enjoy a ‘braai’ around campfires, listen to tales told by the game rangers and then sleep comfortably on the train. The official history of the Park recounts the response:

The passengers declared this the most exciting and interesting episode of the whole tour, and immediately the Game Reserve began to be recognised for the tourist attraction that it was. Col. Deneys Reitz became an enthusiastic advocate of the National Park scheme and so did various other prominent personalities such as Sir William Hoy, the General Manager of the Railways, who requested Stratford Caldecott, an artist, to be the Railways publicity agent for the advertisement of the Sabi Game Reserve as a potential asset.

In 1927 the SAR and the Park reached an agreement on the overall strategy to attract tourists. Co-operation continued between the SAR and the Parks Board well after Hoy’s retirement, but he remains the first person to see the tourist potential of the Park and acted on it.

The rise of the railways men

Sir William Hoy’s rapid rise to senior positions and his influence beyond strictly railway matters is attributable to being the right person in the right place at the right time.

National railways arrived belatedly in South Africa, only when demanded by the diamond and gold industries. But the effect was the same as in many other countries: the growth of the railways propelled individuals to prominence because of the economic and social impact of the technology itself.

Historians of the railways such as Christian Wolmar* identify at least three major impacts of the process.

- The railways reduced the costs of transport of goods, accelerating the time to market and making it possible to link different markets.

- The construction of railways created employment and investment and a demand for goods not previously produced locally. Every level of commerce and industry had to negotiate with the railway authorities to ensure that its interests were met. This made the individuals in railway management well-known and influential.

- In South Africa (and many other countries) railway construction was seen as part of nation-building . The higher levels of railway management as political posts, with the responsibility for ensuring that the benefits of railway connections were supportive of the nation building agenda.

Without in any way diminishing Hoy’s competences, the dynamics of the spread of the railways in South Africa helped to promote his career.

So also did his support of Hermanus. In the period 1900 to 1950 Hermanus was unexpectedly a place that attracted women and men of national and international standing. In turn, some of these figures developed committed relationships with each other, sustained over lifetimes. Through Hermanus, Hoy had personal links with all the Governors-General of his time, with influential politicians and, above all, with Jan Smuts.

Hoy’s successes lay in the fact that he combined a strong link with Hermanus with a high level of personal competence in an important sector of the South African economy during times of conflict, reconciliation, rapid growth and opportunity.

* Wolmar, Christian: Blood, Iron and Gold: How the Railways Transformed the World (2009)

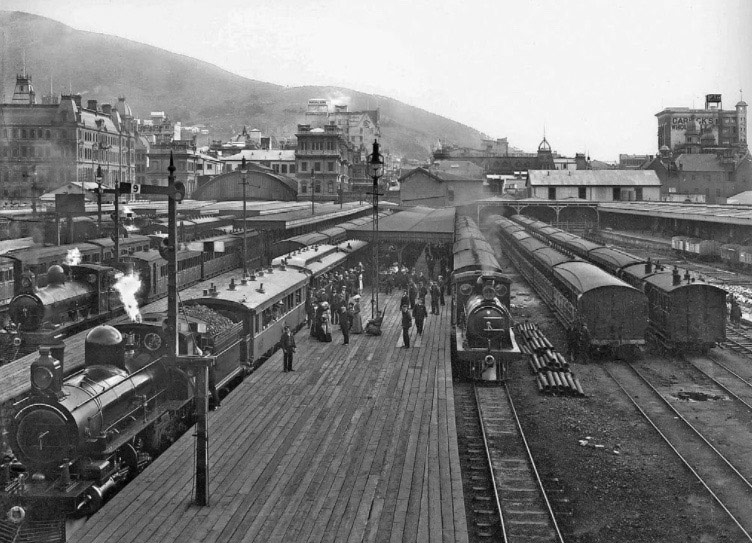

Cape Town station’s switching yard in the early 20th century. Between 1905 and 1907 a photographer, T.D. Ravenscroft, was commissioned to photograph the Cape Colony’s railway stations. (Note the Garlicks building on the right, which at the time was almost on the sea shore before the massive engineering project to reclaim the Foreshore.)

Hoy’s Koppie, where Sir William Hoy and his wife, Gertrude, lie buried.

Sir William Hoy was knigted in 1916, among others for his railway work during Genl Louis Botha’s military campaign in German South West Africa during World War I.

The Colenso project was completed in two years. At the time it was the second biggest railway electrification project in the world.

Date: 03 August 2017